STRUGGLE, THY NAME IS LIFE

I began my journey towards Pakistan from the Ajmer station. It was going to take us four hours to reach Hyderabad via Marwar Junction and Khokhrapar. The stations were small, but there was a large number of people gathered at each one to get onboard or welcome the ones arriving. Though strangers, we felt well-knitted due to our common bond, i.e., Islam. Sindhi Muslims would stand waiting at the stations for the migrants with flowers in their hands. Whenever the train stopped, each one of them would try to reach us first to accord a heartening welcome. If today’s generation was to witness such a gesture, they would sever roots of all racism and linguistic differences. Unfortunately, that isn’t the case. Separate camps were erected for men and women outside the station as a temporary arrangement. Haroon-ur-Rashid’s mother had probably informed him about her arrival, so he promptly received us and took us to his home located in a nearby neighborhood.

His home looked like an apartment, but it felt quite spacious because of so much room in our hearts for each other. I had made up my mind during my stay of two or three days about moving to Karachi. I had nothing in my pocket, but I had the address of my father’s friend Nabidad Khan Awan. I thanked Haroon for all he had done for me and reached the station. There I came across Irtiza Baig Sahab who used to work with my father at the RMS. When he found out about my plans, he took me to a side and gave me Rs10, saying “Keep it, it will come in handy.” I suddenly felt relieved, so much so that I even forgot to thank him. Darkness had descended by the time I boarded a train to Karachi. The train reached the station after two and a half hours, and it was completely dark when I put my foot in the city on August 28, 1947. I had my last meal at Haroon’s house, so now all I could think about was a good sleep. I was walking with a bag full of clothes when I saw more than a dozen people sleeping carelessly on the footpath facing the Cotton Exchange building.

I put my bag underneath my head like them. I was so tired that it took me a little time to fall asleep. I woke up to the sound of Fajr’s azaan (call for prayers). I have never forgotten that first night in Karachi on a footpath. I immediately decided to find Mr. Nabidad’s house. My only clue was a piece of paper with his address on it. I took a tram for the first time in my life. It ran from Saddar to Tower. I finally reached the residential quarters for government officials in Jut Lines. He was now working for the RMS in Karachi. His wife happened to be the daughter of one of mother’s cousins, so they were pleased to see me and were very hospitable during my entire stay. My hijrat was peaceful overall. I had found a shelter too, though not permanent. I started to think about finding work. Besides, being dependent on someone for too long can be bothersome for them. So, I began to reach out to my father’s friends who had migrated from Ajmer. Syed Nusrat Ali was one of them, a kindhearted, polite man. We both met, and he attentively listened to the details of my travel, family’s whereabouts, and the place of stay in the city. Suddenly, he asked me if I was interested in employment. I nodded without sparing a second. The public sector lacked workforce at the time, so one didn’t need a strong referral.

I already knew typing and shorthand. Mr. Nusrat was my father’s colleague in the postal service as a superintendent and a personal advisor to Sardar Abdul Rub Nishtar. He had also introduced me to Sir Nishtar during his visit to Ajmer. Mr. Nusrat also accompanied him when he was appointed minister of communication. With Mr. Nusrat’s help, I was able to secure a role in the income tax department. He sent me to an acquaintance of his and asked him over the phone to hire me if I met the criteria of merit. He also told me to never use a referral to progress in life. It had hardly been a month working there and I was yet to get the appointment letter when I came across an advertisement in daily Dawn regarding a vacancy in Habib Bank. I raced towards the opportunity without intimating anyone. I went to the bank’s head office situated on Napier Road. The candidates were being interviewed by an officer with the name of ‘Peer bhai’. On my turn, he told me to write a dictation and then read it out. I did so without looking at it, thanks to the God-gifted memory. He was really happy to hear it and took me to his office. There, he handed me a bunch of pending letters and asked me to type them. I was able to hand him a lot of them because I was good with the keyboard. I got the job! I continued to stay at Mr. Nabidad’s house for the next nine months during my employment.

My next job was at Greeks Salt, which extracted salt from seawater. The office was situated near Tower. The quest to find the best took me to Greaves and Compton, Denso Hall where I worked for a remuneration of Rs175 a month. My next destination was Harkinson Limited where I was paid Rs190 a month. Later, I decided to leave them for Aluminium Pakistan with its office facing Tower. After some time, I opted for Sindh Purchasing Board. This semi-government company used to export grains from Sindh. Here, I worked as a subordinate to a short-tempered general manager. He had served as a deputy commissioner in Nagpur and was full of the usual bureaucratic traits. Jamshed Nusserwanjee Mehta, who had served as Karachi’s mayor in 1930 after a formal separation from Mumbai, was in the driving seat. I would go to him to take notes, representing the general manager. After a few days, he asked me to take the dictation on his way back from work to save time. I used to be so immersed in taking notes that the distance to his home felt rather short. When we reached there, complainants would already be in the spacious lawn of his large home. Mr. Mehta would meet them one by one and issue orders on the spot. I was beginning to settle in the new country. I went back to Shahjahanpur in 1948, brought my younger brother Aleem with me, and got him enrolled in the CMS High School, Burns Road in fourth grade. Now, as we were two, I began to seek a place to live. Despite Mr. Nabidad’s insistence, I went on with my search and eventually settled for an old house in the PIB colony for a rent of Rs25. All it had was a small room, some open space, a bathroom, and a shower. After some time, when the landlord got the place vacated for rebuilding, we rented a room in Lyari where we lived for some time.

This house was far from my office, so we rented two charpoys in Maulvi Musafirkhana situated at Bandar Road near Nigar Cinema. The place where the mausoleum of Quaid-e-Azam is today was called Quaidabad at the time. A few weeks later, I bought an eight to 10-feet-wide weeded shack there. Since our arrival to Pakistan, we were urged by many to file a claim to have a house allotted in Karachi for the one we had left in India. Some even suggested that we file a false claim to get a bigger house in return. I turned down every such advice and filed nothing, not even for a small house. Instead, I thought of my shack as my only asset and pledged to work hard to build my house with my own finances.

Is This Your Home?

I was now the ‘owner’ of my piece of ‘land’. I built a bathroom and a shower utilizing the space available. A lantern was the only source of light in the ‘house’. As for water, I used to get the canister refilled from a public tap every morning before work. Realizing that we had all the ‘facilities’ now, my younger brother wrote to my mother, telling her she could move to Karachi with everyone without delay since “bhai sahib has his own house now”. She arrived with her younger children a few days after receiving the letter. She understandably wasn’t happy with what she saw. “Is this your house,” she asked. The fact is I had already been thinking about finding a government job to be eligible for a house, and her scold turned my thoughts into a decision.

This time, I got employed at the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) operating under the Ministry of Defense. My joining was in the directorate facing the press club. Adjacent nearby were some other offices of the ministry, while the federal secretariat was close to passport office near Khizra mosque. Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan was the first Prime Minister of the country. The government invited the king of Iran for an official visit. His visit to the ISI office was also a part of the itinerary. Colonel Yaqub Khan was the in-charge of the intelligent services and was later appointed as Lieutenant General. He also served as the governor of erstwhile East Pakistan and as the Foreign Minister in the 80s. He was relentlessly disciplined and short-tempered. As the vehicle carrying the king stopped in front of him, he stepped forward to welcome him. That’s when a tea boy carrying a cup came out of nowhere! The colonel felt humiliated at the breach of protocol. All he could do in a fit of anger was to raise the child in his arms in the air and put him back. I was watching all of this from my room. I thought in that moment that it wouldn’t have happened had it been a civilian. However, when I later had an opportunity to observe him closely, I found him to be really kind, humble, and a literary and decent man, a distinct personality amongst the officers. Indeed, one incident cannot determine a person’s personality.

The ISI used to operate quite differently and in a limited manner, but Indian activities were still closely monitored. The place where I lived was close to the office and a mosque was nearby. The rainy season had set in. I decided to offer Asr prayers there before leaving. As soon as I started the prayers, I heard a terrifying thunder. I knew that the downpour would shatter my little ‘nest’. I hurriedly completed the prayers, pulled my pants up, and rushed towards my shack located in a low-lying area near Quaid’s mausoleum. It was half-submerged by the time I reached there. I could hardly get inside. I saw my mother struggle with a stove on a charpoy to prepare food. She started to cry as soon as she saw me. My siblings stood in a corner looking at me helplessly.

We had to deal with the stagnant water for several days before it was drained out by municipality workers. An individual with the name of Latafatullah lived near our shack and my mother knew his family. He sent a marriage proposal for Azizah, second among my sisters. Despite knowing that he didn’t have any job as such, we accepted his offer purely on the basis of his character. We waved her goodbye with a few dresses and kitchen utensils. My brother-in-law later secured a role at the Foreign Office. He was then sent to Thailand, where he went with Aziza. Their first daughter was born there. The second one is now Mushtaq Yusufi’s daughter-in-law. The city’s administration provided us and other people of the locality with homes in Jacob Lines on rent. A quarter was also allotted to Latafatullah. Six months later, I was transferred to Air Headquarters which was situated within the Mauripur airbase. We were required to report at the office at 6:30 am. A military truck would pick up the servicemen and civilians from Numaish. I used to walk to the bus station, only to find the seats full. I would make the rest of the travel standing. I was earning nearly Rs200 then. It was hard to manage an entire family’s expenses, so I began to look for a part-time job. The next few years were particularly hard for me during my part-time employment at Barlas Brothers, ARG Khan, and Shareef & Brothers.

As per my routine, I would board a military truck to McLeod Road. I would offer Zuhr prayers at the GPO mosque, have lunch in a corner, take some rest there, and leave. I was required to report at the first part-time job by 3:00 pm, and leave at 5:00 pm for the second at Barrister Asghar’s office. I would be completely devoid of energy when returning home by 9:00 pm. The next day would bring back the same routine, except for the weekly off when I would sleep carefree. One day, a neighbor advised me to study further. It was a useful suggestion so I decided to give it a thought. I joined Munshi Fazil (Persian language) program nearby. The other two programs offered were Maulvi Fazil (Arabic language program), and Urdu Fazil. The educational system was in place under the supervision of Punjab University.

Though I acted on the good advice, I couldn’t extract time being busy with three jobs. I used to study while standing in the truck on my way to work, keeping the book in one hand and holding the pipe installed on the roof of the bus with the other hand. I endured the hardship to not only complete the course, but also my intermediate and Bachelor’s in Arts (BA). One day, I got a day off from the office to visit Islamia College where I signed up for the two-year MA program to study arts courses. It wasn’t possible to take classes, given the rigorous work routine. Time flew and there I was looking at my result; I had made it through with a second division. When Barrister Asghar urged me to do LLB, I told him it wasn’t possible. He replied, “Everyone has to take a dive in the river, regardless of whether they get out alive.” These words revived my focus and I chose SM College for my pursuit in law.

But here, too, I couldn’t attend the classes and no one asked either, thank God. Meanwhile, houses for government employees in Jacob Lines had been built, so we moved there. My elder sister had settled in Kotri. She lost a lot of blood due to a complication while giving birth, and died. It was devastating for us, especially for my mother who had lost her beloved daughter suddenly. But Allah had blessed her with patience and fortitude abundantly. After some time, she herself got Riazullah Khan, her daughter’s husband, remarried. I was progressing with my law degree despite the lack of familiarity with the classroom or the lecturers. It hadn’t concluded when I signed up for a Diploma in Journalism from the University of Karachi. It proved easy to enroll in the course, but circumstances weren’t the same as before. Head of the department Professor Sharif-ul-Mujahid was inflexibly firm in terms of discipline and principles. Fazal Qureshi was one of my classmates and lived next to the Jacob Lines post office. His job routine was similar to mine and he, too, would regularly skip lectures. We got to work as trainees in many newspapers those days. I was sent to United Press of Pakistan (UPP) and Fazal went to Pakistan Press International (PPI). While working there, I had the honor of interviewing Maulvi Abdul Haq, titled ‘The Father of Urdu’.

The exams were right around the corner, but we were continuing our routine as usual. I was coincidentally inside the campus one day when I was spotted by Professor Sharif. He instantaneously said, “What are you even studying if you don’t attend the classes. I won’t allow you at all to take the exam on such minimal attendance.” That academic year went to waste! I prepared as much as I could the next year and managed a third division. On the other hand, Fazal Qureshi showed such enthusiasm during his training at PPI that the opportunity turned out to be an employment of a lifetime for him. Such a bond with a journalistic organization is seldom seen. I always felt proud of my deep association with him. I got my LLB degree in 1956. I had a dream of becoming a government officer right from my days of adolescence. The Indian Civil Service (ICS) was known as the most credible institution those days. Those who would pass its exam would become high-ranking officers with an elevated status in society. I hadn’t abandoned my dream even after arriving in Karachi.

Likewise, it was considered an honor at the time to appear in the exam of the Pakistan Administrative Service, and it required rigorous preparation. I attempted the 1955-56 annual test. I was still working at Air Headquarters at the time. I passed the written exam on the first attempt, whereas it took many candidates two to three years to get through it. I had a Karachi domicile and the seats were fewer even then. I failed the interview. It is obvious that the successful ones were better than me.

In the second attempt, I was declared ‘overaged’ by a day. I tried my utmost to resolve the issue but couldn’t. Our officer N.M Khan, Chief Secretary of erstwhile East Pakistan, was an admirer of my professional struggle and a well-wisher for me. I talked to him, and he wrote to his friend, Chief of the Service Commission, “Mr. Naimatullah Khan, about whom I am writing this letter, was born one hour before he should have. You will agree with me that it’s none of his fault.” Despite this intimation, I wasn’t allowed to appear in the exam, and my dream of becoming a government officer couldn’t be materialized.

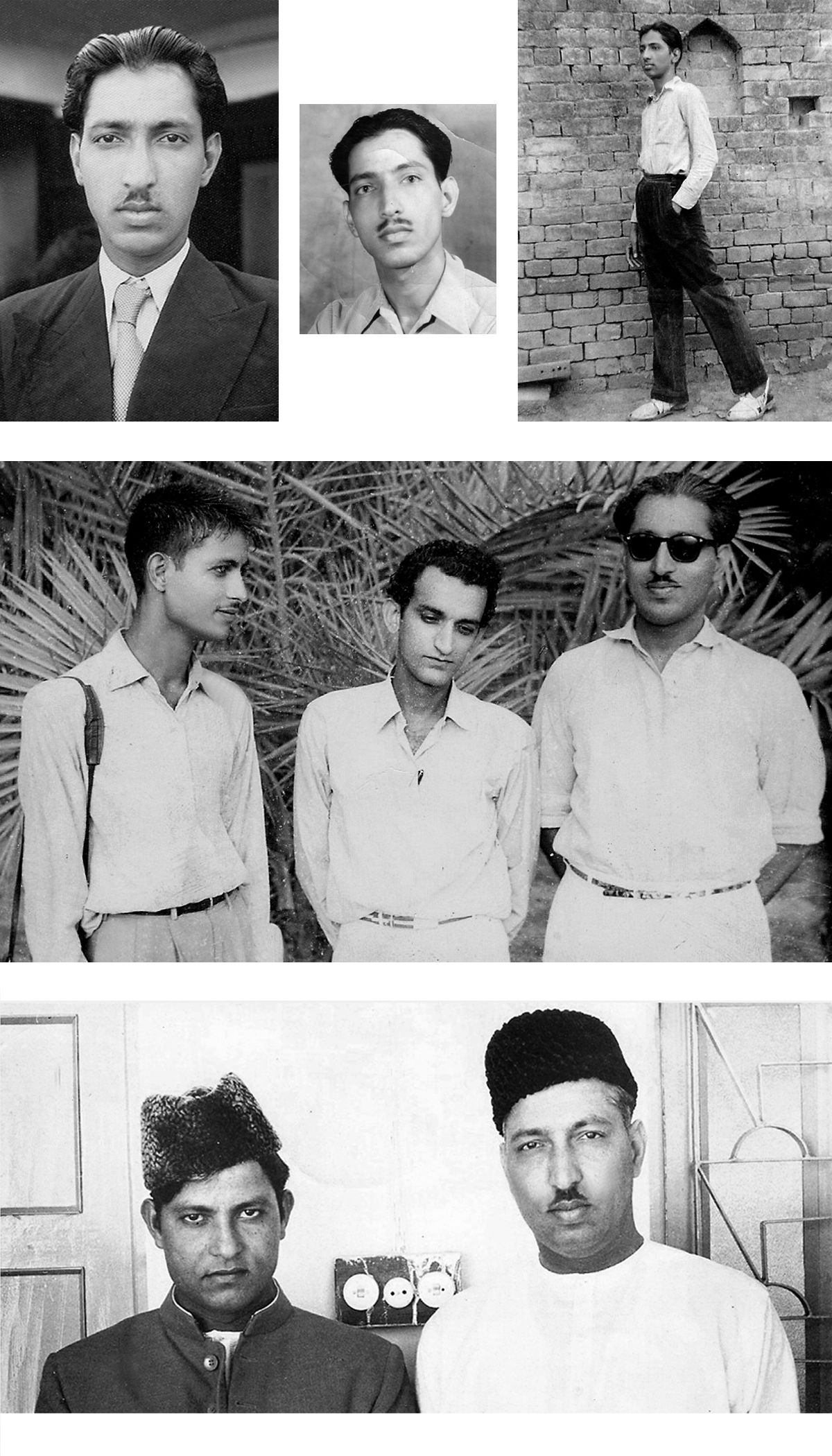

Some Glimpses From Young Age

![]()